Shambhala and the Kagyu Lineage

January 21, 2009

Commentary by Jim Wilton

The Sakyong’s activity is clearly focused these days on developing the Shambhala path through to the practices of the Scorpion Seal retreat. Since my practice has been almost entirely focused on Kagyu Buddhist practice in recent years — I feel somewhat left behind. For example, the Sakyong’s retreats starting this year will no longer have a “track” for Vajrayogini practice. So my choice is to join Werma practice or not to participate. For me, it will probably be a few years before I can circle back and fully engage with Werma practice and the Scorpion Seal path.

I don’t view the Sakyong’s approach as a move away from Kagyu Buddhist practices as much as a move toward Shambhala practices — recognizing that we are the sole holders of Shambhala terma and that time is short. I write this because I was recently reading Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche’s autobiography Blazing Splendor and found a similar tension expressed regarding Rinpoche’s Barom Kagyu lineage and his unquestioned primary focus on propagation of Chökyur Lingpa’s New Treasures terma. Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche expresses some regret and wistfulness in acknowledging that his lineage’s one pointed focus on the New Treasures has resulted in a lack of attention to traditional Barom Kagyu practices (other than certain protector practices).

This experience seems to me to be in some way similar to the situation in our mandala. I know that there are practitioners who regret both the connection of Shambhala and Buddhism as concepts and the perceived neglect of the Kagyu Buddhist lineage — which in CTR’s vision was passed to VROT as lineage holder. And perhaps Kagyu practices will become an “advanced” practice in our mandala for old students. This in some sense is a shame because CTR’s extraordinary teachings on Vajrayogini and the excellent annotated sadhanas that we use for Kagyu yidam practices are currently unavailable to other Kagyu sanghas and increasingly will be underutilized in our sangha. I don’t think that we are yet at the point where we are neglecting Kagyu practices (although I expect our feasts may have sparser attendance as newer practioners defer practice of Kagyu ngondro in favor of the Shambhala path).

However, it would be a greater tragedy to fail to fully transmit the Shambhala terma. These are my mixed feelings. I don’t know if others have thoughts about this. I’d be interested in hearing them.

Jim Wilton is member of the Boston Shambhala Center since 1986. He lives in Newton, Massachusetts with his wife Erika and son Nick.

On Divisiveness

January 19, 2009

Commentary by Barbara Blouin

I don’t remember when the dreams began. For a long time I dreamed that a practice center where I had practiced many times had become unrecognizable, even alien, to me. The details of these dreams are too long for this commentary, but my dream-feeling was one of penetrating sadness, loneliness, and irrevocable loss.

For years I didn’t understand what those dreams meant. Then gradually, my waking experiences of walking into my local Shambhala Centre (Halifax) started to resemble my dreams. I felt like I no longer belonged, and in ways that were partly specific and partly indefinable, the centre felt foreign to me. I felt that, in that place, the presence of my root guru, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, which I had always experienced so strongly, was waning, that it was being lost.

Several months ago I became involved in the creation of this web site, to which I contributed two articles. When I first started going to the meetings that culminated in the web site, I said, “I’m afraid I could lose some friends because of this,” and this fear has, in fact, become a reality with one person. I have deeply upset another friend. They and others see my role, and that of RFS, as divisive. That is painful to me and even more painful to them. I regret that I have caused my friends pain and wish I felt I had a choice, but what I was doing seemed — and still seems — choiceless.

Those who are upset about Radio Free Shambhala see our “divisiveness” as damaging to the fulfillment of the Vidyadhara’s vision, as disrespectful of the Sakyong, and as harmful to the sangha. They say that we are creating a “schism,” a “faction.” What they seem to fail to recognize — and I find this odd — is that the sangha is already divided. It has, in fact, been divided for a long time.

Does divisiveness (I am calling it by the label that others have chosen, although I would not choose it) inflame already existing divisions? Should I and others stop taking actions because some regard them as divisive? Should we keep our thoughts to ourselves and keep our pain inside? Do we even have a right to speak out publicly?

The subject of divisiveness was explored and debated for three days by the Mandala Governing Council in Boston in December, 2004, just over four years ago. The statement that was drafted after this meeting, called The ground of openness and trust (PDF) is found in the Members’ section of the Shambhala web site.

The contents of this statement address divisiveness head on:

The Mandala Governing Council, meeting in Boston from 4 to 7 December 2004, wishes formally to affirm that the continuing emergence of Shambhala Society must be based on the profound realisation of unconditional openness and trust in basic goodness that are the heart of our Kagyü, Nyingma, and Shambhala lineages. …we urge our community at all levels to reflect on the ways in which we can create containers for sane society within our mandala. Thus we can work compassionately with our differences and conflicts, so that there is respect for each other’s commitment to different streams of teachings and practice. No one should face derision, exclusion, rejection, or retribution for holding or expressing their views or for dissenting from the views held by others, including the policies and practices of the leadership of the mandala. … The process of community reflection and renewal in which we are now engaged must be conducted in such a way that it includes all generations, embracing elders, emerging leaders, the second and third generations, as well as those who feel they have been marginalized in our community over the years.

As Shambhalians, our trust for the Sakyong varies widely from individual to individual. At one end of the continuum, a number of devoted students are deeply concerned that the Sakyong is systematically dismantling the Vidyadhara’s vision. At the other end of the continuum, equally devoted students feel the Sakyong is completely and brilliantly manifesting the Vidydhara’s vision.

The sangha is divided because there are a great many students of Chögyam Trungpa who “are deeply concerned that the Sakyong is systematically dismantling the Vidyadhara’s vision.” These students cannot, however, be described as a group, or lumped together. They have no organization, no web site (RFS notwithstanding), no way to communicate with each other except one by one, or in small informal local groups. They have no place in which to gather.

Yet I would go so far as to say that they — we — are a sangha, a disenfranchised sangha that exists both within and outside the Shambhala organization. No one knows how many of us are out there. According to one estimate, as many as 70 % of Chögyam Trungpa’s original students have left Shambala International. In my opinion that estimate is too high, but whatever the number or percentage, there are a great many such students. Some remain members of Shambhala Centres, while others have stopped paying dues. Some have completely cut their ties with the organization, while others continue to go to programs and to practice at urban and practice centres. There is no way to create a profile of a typical, for want of a better word, “disaffected” sangha member. My hope is that those who disagree with their views have not simply dismissed them, written them off.

The divisiveness issue came to a head recently in Halifax because members of a local group devoted to Chögyam Trungpa announced a meeting to discuss the idea of forming a delek (working title: CTR Delek). We asked to hold the first meeting at Coburg House, which is a complex of four buildings. Everyone in Coburg House is a participant at the Shambhala Centre, although some only at the level of open house. Permission was given and an announcement was posted on the nova-scotia-announce mailing list that the meeting would take place on Sunday, January 18. That announcement provoked a heated controversy, and the Coburg House offer was revoked. Some people felt that calling this group a delek was improper. The delek system, they claimed, was based on neighbourhoods, and because this group was not neighbourhood-based it could not rightly call itself a delek.

This is not the place to go into the details of the opposition to the formation of the CTR Delek. Probably few of us remember, or ever knew, that in 1982, Chögyam Trungpa, who created the delek system, told his students at Seminary:

I want you to know that we are not setting up a solid and fixed idea about how things should run, how things should go. We are giving a lot of leverage and a lot of freedom to you people to decide how you would like your sangha, your world, your enlightened society to function. We are leaving a lot of it up to you. The responsibility is yours, people, all of you, to elect dekyongs and come into the delek system altogether. So it requires a lot of your involvement.

Would Chögyam Trungpa have approved, or disapproved, of what we are doing? It’s an open question.

After the announcement of our delek meeting at Coburg House, Nick Wright, a resident, sent a private e-mail to Madeline Schreiber, the Coburg House manager. Nick has given me permission to quote his letter and to use his name.

I noticed that Mark Szpakowski’s invitation to form a “Chögyam Trungpa delek” mentioned Coburg House as the meeting place. I have some questions.

1) Why are they not using one of their houses? … Are you inviting them here because you support their views?

2) Why are we hosting a group that is working hard to undermine the Sakyong? I don’t think it is good for Coburg House to be associated in people’s minds with that kind of energy and intention. Respectful disagreement is one thing, active subversion is something else again.

3) Why is Coburg House fostering the formation of a faction within Shambhala — which is the clear intention of this group? Their arrogation of the name “Chogyam Trungpa” for their proposed deleg makes that abundantly clear. All of the Vidyadhara’s students feel we are carrying on his legacy, from the Sakyong on downward. It is merely offensive that any sangha group is arrogant enough to presume that they are “the true holders of his legacy”; I feel it is dangerous (for them and newer students) to give them encouragement and support in such a view.

I have chosen to reprint most of his letter because I think Nick has clearly articulated some of the objections, not only to the CTR Delek, but, more broadly and more importantly, to the existence and purpose of Radio Free Shambhala and its ilk. He is far from being the only sangha member who has problems with this web site and its views.

This letter provides plenty to chew on, partly because a number of assumptions are made about the organizers of the CTR Delek:

- We are working hard to undermine the Sakyong.

- Evidence for this is abundantly clear and an arrogation of the name ‘Chögyam Trungpa’ for our proposed deleg. (According to the Oxford English Dictionary: arrogate means to “take or claim [something] for oneself without justification”).

- We are engaged in active subversion.

- We are fostering the formation of a faction within Shambhala–which is [our] clear intention.

- We are arrogant : It is merely offensive that any sangha group is arrogant enough to presume that they are ‘the true holders of his legacy’.

- Our goals are dangerous.

Since the sangha is already divided, can an argument be sustained that “we” of RFS are causing divisiveness? To me, this is the key point, and I don’t think it holds up to scrutiny. How can something be divided that has already divided itself?

I think the same can be said of the accusations that “the formation of a faction” is our goal, and that we are “actively working to undermine the Sakyong.” There is in fact no faction. The many disaffected sangha members do not belong to a group or an organization; they are simply a collection of individuals. If it were possible to gather them together in a large room and have a discussion, I’m sure they would find plenty to disagree over. There is no unified view.

We — in this case, a small collection of disaffected Halifax sangha — are not “subversive” because we have no hidden agenda. The purpose of Radio Free Shambhala is clear:

Radio Free Shambhala is not affiliated with Shambhala International, a Shambhala Buddhist church. It has arisen because many people, both within and outside that organization, are looking for further means to connect to and to fulfill their inspiration, to think bigger. This is true for those whose emphasis is on the Buddhadharma way and lineage of Chögyam Trungpa, and for those who may or may not be buddhists, who see his Shambhala Vision as a secular/sacred way of meeting this world and society. We hope that the Radio Free Shambhala web site will be one of many vehicles for communicating about this view, its practice, and its action in this world.

The intention of Radio Free Shambhala is simple: to provide an open space for practitioners of Shambhala Vision. We are hosting your voices, but may not necessarily agree with any particular view. We will, however, work with you to protect the genuineness of that open space, through all that we are learning about right speech, decorum, conquering aggression, and action in the world.

If you, who are reading this article, think that this purpose is subversive or sinister, we would like to hear from you. Granted — subversiveness can be sinister. I went again to the OED for the definition. Subversive means “seeking or intended to subvert an established system or institution.” We have no such intention. There are plenty of obvious examples of subversive activity. The first one that comes to my mind is the CIA, which has organized and carried out numerous plots to overthrow legitimate, democratically elected governments.

I hope that by this time I have made my point. There is no need to address all of the accusations made in this e-mail. What strikes me most about the language is the fear that lurks behind it.

Radio Free Shambhala is threatening to Nick Wright and to others, but so far, none of our critics has used the word “fear.” No one has said: “I am afraid of what you are doing,” although Nick Wright has called us “dangerous.” The fear, I think, may be twofold: the continuation of the legacy of Chögyam Trungpa is being undermined, and Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche and his teachings are under attack. These two go together, because loyalty to the Druk Sakyong is often interpreted as automatic loyalty to the current Sakyong. Loyalty in this sense is a huge subject that I would like to see as the basis for another RFS article.

It is important to surface the subject of fear because, I believe, it lies at the bottom of most of the criticism of the RFS web site and the efforts to create a CTR Delek in Halifax. As we all know, fear provokes a variety of responses. At the most basic, physiological level, fear triggers fight or flight or freeze, and I believe this is at the root of the anger that RFS has provoked. Two responses to my article Navigating the Labyrinth are useful in understanding the controversy — including the fear —that my article, and RFS in general, have generated. It is noteworthy that this exchange is between two second-generation sangha members. Nyima Wimberly wrote:

I still find it hard to believe that there is this hateful contingent of sad, bitter students who are so driven to twist anything Shambhala into an evil act. Can you see yourselves becoming zealots?

Andrew Speraw responded:

Why does it have to be either the Sakyong is ‘up to no good’ or people who question are ‘up to no good’? Why do we undervalue the process of debate? Is there really something to be afraid of or something that we need to protect against? Is it really necessary to bring things to that painful point? In an enlightened society there is a place for both questioning and devotion. We need to learn how to open our hearts to those who both agree and disagree with our views. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche did not promote blind faith and I think you need to respect the process of questioning that some people are going through. They may or may not become students of the Sakyong and that is OK. Trying to silence those who hold different views will only result in further division.

To end this commentary, I ask that those who are upset and angry with RFS, and those who have been supportive of the view of RFS, open their hearts and listen to what Andrew Speraw is saying. Loyalty is not dogmatism; questioning what the Sakyong is doing is not subversive; wanting to meet outside the umbrella of the organization is not factionalism.

And I ask that all of us be more open to really listening to each other with open hearts. Just listen. We all have something to say that is worth hearing.

Self-Improvement, Windhorse, and Spiritual Materialism

January 2, 2009

Commentary by Andrew Safer

It’s normal to have ambitions, goals, and expectations when one enters the spiritual path. At 15, I was fortunate to go on a family vacation with my mother and sister to Tassajara Zen Mountain Center where I met Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. I was immediately struck by him. Whatever he had–composure, equanimity, fathomlessness, big mind–I wanted it. Later, when I was in university, I sat zazen with Kobun Chino Sensei and Jiyu Kennett Roshi.

It’s normal to have ambitions, goals, and expectations when one enters the spiritual path. At 15, I was fortunate to go on a family vacation with my mother and sister to Tassajara Zen Mountain Center where I met Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. I was immediately struck by him. Whatever he had–composure, equanimity, fathomlessness, big mind–I wanted it. Later, when I was in university, I sat zazen with Kobun Chino Sensei and Jiyu Kennett Roshi.

Zen training was uncompromising. I soon found out that what I was hoping to achieve was beside the point. What kept coming back was: just sit! When I started studying with Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the practice environment was less severe, but the message was the same. The sitting practice of meditation was always paramount. What I was striving for—my version of enlightenment—was, well, hardly the point. Over time, I started to learn that there was a great distance between what I wanted, and reality.

My sense is that the same is true of any authentic spiritual path: it’s not about what the practitioner wants. It’s about the practice itself, contacting a bigger world, and dedicating oneself to others.

When I recently read Ruling Your World by Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche I found much of the book instructive, but I was also concerned because there are many instances where the four dignities and the practices are spoken about in terms of the result: if you do A, then B will happen. While this approach will interest the beginner who is achievement-oriented, I’m concerned that it is sending the wrong message to that same person who rereads the book once they’ve entered the path, and to everyone else who reads it.

My reference points are my early teachers and my root guru, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. In Zen Mind Beginner’s Mind, Suzuki Roshi says (emphasis mine):

Especially for young people, it is necessary to try very hard to achieve something. You must stretch out your arms and legs as wide as they will go. Form is form. You must be true to your own way until at last you actually come to the point where you see it is necessary to forget all about yourself. Until you come to this point, it is completely mistaken to think that whatever you do is Zen or that it does not matter whether you practice or not. But if you make your best effort just to continue your practice with your whole mind and body, without gaining ideas, then whatever you do will be true practice. Just to continue should be your purpose. [p 43]

It is therefore a bit jarring to read, in the chapter in Ruling Your World on “The Confidence of Equanimity”: “We realize in an outrageous moment that if we approach all beings with kindness, appreciation and love, we can be happy anytime, anywhere.” [p 138]

As Suzuki Roshi said, “just to continue should be your purpose.” When one’s own happiness is brought about by an act of kindness, this seems to be a different kettle of fish entirely. (This theme was also explored in Not About Happiness.)

When we take the bodhisattva vow, we vow to liberate all sentient beings before ourself. Even though it’s impossible, we vow to do so. This is not only the height of magnanimity, it’s also pragmatic, because it sidetracks the practitioner from thinking of himself. Pragmatic, because this way, he doesn’t waste any time thinking about, or catering to, his ego—which, as we eventually discover, in fact, doesn’t exist.

The theme of killing two birds with one stone—serving oneself while serving others—reappears throughout the book. In the chapter on “The Confidence of Delight in Helping Others”:

We may be sitting there contemplating others, and in the back of our mind thinking: “I need to do more for myself.” By thinking of others, we are doing more for ourselves. Generating joy by helping others is a secret way—and the best way—of helping ourselves. Every time we think of someone else’s happiness, we are taking a vacation from the “me” plan. It’s like getting physically fit by helping our neighbour shovel the snow from the driveway. [p 116]

In the era of new-age this and new-age that, perhaps it’s fitting that the Buddhadharma and Shambhala teachings have been repackaged in a way that appeals to “the marketplace.” One could argue that this represents a skillful means, that in this way, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche is making the teachings accessible to many more people. This may indeed be the case, but at what cost?

On the topic of self-improvement and the achievement of goals, Trungpa Rinpoche said (emphasis mine):

Trust and compassion for oneself bring inspiration to dance with life, to communicate with the energies of the world. Lacking this kind of inspiration and openness, the spiritual path becomes the samsaric path of desire. One remains trapped in the desire to improve onself, the desire to achieve imagined goals. [Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism: p 98]

Windhorse (lungta in Tibetan)—the self-existing energy of basic goodness that has been described as “the breeze of delight”—is an important theme in Ruling Your World. Once again, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche breaks new ground in the way he discusses this key Shambhalian principle. “We are not afraid of the power of windhorse, which brings worldly and spiritual success.” [p 179]

Clearly, this is a description that will appeal to the self-improvement types. But even in the context of a new-age version of windhorse which is all about “what’s in it for me?”, this description is one-sided. Consider this passage by Trungpa Rinpoche from Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior:

The warrior who experiences windhorse feels the joy and sorrow of love in everything he does. He feels hot and cold, sweet and sour simultaneously. Whether things go well or things go badly, whether there is success or failure, he feels sad and delighted at once. [p 85]

In the last pages of Ruling Your World, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche expands on the outcomes of windhorse:

Windhorse brings spiritual and worldly success—personal power, harmony with others, strong life force, and material prosperity. [pp 192-193]

The notion that spirituality can be used to attain one’s personal goals was anathema to Trungpa Rinpoche. He made this quite clear in his ground-breaking book, Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, which was published in 1973.

It would be foolish to study more advanced subjects before we are familiar with the starting point, the nature of ego. Speculations about the goal become mere fantasy. These speculations may take the form of advanced ideas and descriptions of spiritual experiences, but they only exploit the weaker aspects of human nature, our expectations and desires to see and hear something colorful, something extraordinary. If we begin our study with these dreams of extraordinary, “enlightening”, and dramatic experiences, then we will build up our expectations and preconceptions so that later, when we are actually working on the path, our minds will be occupied largely with what will be rather than with what is. It is destructive and not fair to people to play on their weaknesses, their expectations and dreams, rather than to present the realistic starting point of what they are. It is necessary, therefore, to start on what we are and why we are searching. [pp 121-122]

The results-based orientation of the Sakyong’s teachings and his appeal to the self-help market are key characteristics that distinguish him from Trungpa Rinpoche.

Having coined the phrase “spiritual materialism,” Trungpa Rinpoche defined it in this way:

There are numerous sidetracks which lead to a distorted ego-centered version of spirituality; we can deceive ourselves into thinking we are developing spiritually when instead we are strengthening our egocentricity through spiritual techniques. [p 3]

He was particularly diligent in pointing out the pitfall of self-deception so that the practitioner can be aware of it and recognize it when it rears its ugly head.

Ego is very professional, overwhelmingly efficient in its own way. When we think that we are working on the forward-moving process of attempting to empty ourselves out, we find ourselves going backwards, trying to secure ourselves, filling ourselves up. [p 56]

“Self-deception is a constant problem as we progress along a spiritual path,” continues Trungpa Rinpoche. “Ego is always trying to achieve spirituality. It is rather like wanting to witness your own funeral.” [p 63]

Reading further in Ruling Your World, in addition to happiness, personal power, and worldy and spiritual success, luck is also identified as an outcome for those who practice the path of virtue. This is articulated in the following two passages:

As the golfer Ben Hogan once said, “The more I practice, the luckier I get.” In Tibet, this luck is known as tashi tendrel—auspicious coincidence. [pp 158-159]

By acting virtuously, exerting ourselves in service to others, we are blessed in return by harmony and good luck. [p 160]

From a conventional point of view, there’s no argument here! But is it dharma?

Again, in Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, Trungpa Rinpoche comments on this orientation towards results (emphasis mine).

So the point we come back to is that some kind of real gift or sacrifice is needed if we are to open ourselves completely. This gift may take any form. But in order for it to be meaningful, it must entail giving up our hope of getting something in return. It does not matter how many titles we have, nor how many suits of exotic clothes we have worn through, nor how many philosophies, commitments and sacramental ceremonies we have participated in. We must give up our ambition to get something in return for our gift. That is the really hard way. [p 80]

This passage echoes a well-known line in Trungpa Rinpoche’s Sadhana of Mahamudra : “I make these offerings without expecting anything in return, and without hope of gaining merit.”

The contrast between the teachings of father and son is extreme. Of course, it is Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche’s prerogative to teach as he sees fit. But the fact that the apple has fallen so far from the tree is worth noting, in the interests of helping to preserve the legacy of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche for both present and future generations.

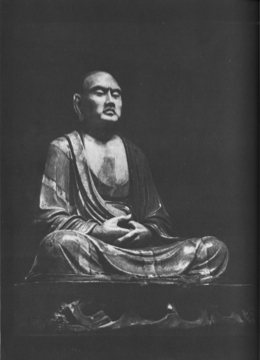

Photograph of Lohan by Robert Newman. The Karme-Chöling shrine room has a series of Lohan images.